Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Good Samaritan law could have cleaned up Gold King, but Dems want reform

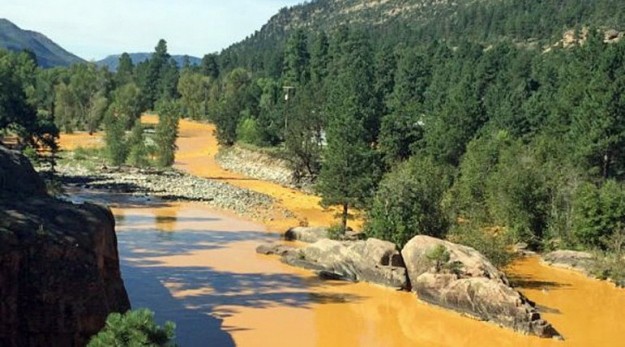

Animas River spill rekindles debate over long-term cleanup of abandoned mines

Editor’s note: A version of this story first appeared in The Colorado Statesman:

A little over two weeks after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and contract workers accidentally released 3 million gallons of acid mine waste into the Animas River, lawmakers are gearing up for a deluge of debate over how best to solve the problem of thousands of abandoned mines leaching into watersheds all over the West.

Experts on mine waste cleanup efforts expect renewed interest in U.S. Rep. Raul Grijalva’s Hardrock Mining Reform and Reclamation Act of 2015, which the Arizona Democrat introduced in January and has been languishing in committee since February.

Grijalva’s bill, which is cosponsored by 25 other Democrats, including Colorado Reps. Jared Polis and Diana DeGette, would require royalties for hardrock mining operations on public lands, create a fund for cleanup of abandoned mines such as the Gold King Mine near Silverton and includes a Good Samaritan provision to absolve third parties of liability for cleanups.

Colorado’s Republican lawmakers are focused on Good Samaritan legislation separate from Democratic efforts to reform the 1872 Mining Act, which – unlike coal, oil and gas mining – does not require companies to pay royalties for extracting hardrock minerals such as gold from federal lands.

“We have known for a long time that mining regulations are absurdly outdated and leave many problems for local communities long after mining operations stop,” DeGette said in an email statement to The Colorado Statesman.

“It should not have taken a dramatic event such as Gold King to get western policymakers thinking seriously about these issues. If we can replace policies from the Ulysses S. Grant administration, we may be able to prevent future disasters and looming threats to the West’s special places.”

But Republican Rep. Scott Tipton, whose Western Slope district includes the area of the spill, wants to see Good Samaritan legislation only. He sponsored an unsuccessful House version of a bill in the last Congress that former Sen. Mark Udall, a Democrat, introduced in the Senate.

Tipton spokesman Josh Green said Grijalva’s bill has little chance of passing in the current Republican-controlled Congress, which reconvenes after Labor Day.

“The Good Samaritan approach is a far more effective way to expedite the cleanup of abandoned mines,” Green told The Statesman. “[Tipton] is currently working with community leaders and stakeholders, as well as with Colorado’s U.S. Senators, toward a similar solution to address the issue that stands the best chance of passing through Congress.”

Good Samaritan legislation would give third-party groups such as state and local governments, nonprofit groups and mining companies binding legal safeguards to remediate abandoned mine sites, many of which date back to the late 19th century.

Udall tried for years to pass Good Samaritan legislation and reform the 1872 Mining Act, meeting resistance from his own party in the form of former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, whose home state of Nevada is one of the most mined in the nation. Udall’s successor in the Senate, Republican Cory Gardner, says he’ll take up the issue after the break.

“I am working on bipartisan solutions that create a number of tools to jumpstart mitigation and get to work on the long backlog of abandoned mines,” Gardner said in a statement to The Statesman. “Each proposal requires careful consideration, but it’s time such policies move beyond introduction and actually move into implementation.”

New Mexican Democratic Sen, Martin Heinrich told the Albuquerque Journal last week that he’ll introduce 1872 Mining Act reform in the Senate this fall. Colorado’s Democratic senator, Michael Bennet, told The Statesman he’s supported reform efforts in the past and is likely to do so again this session.

“Right now, we’re still tackling the immediate health and environmental effects of this spill and investigating the actions that led to the spill,” Bennet said. “But it’s time to start thinking about the bigger picture and the serious issue of legacy mine contamination in the West.

“We need to consider reforming and updating the Mining Law of 1872 and revisit the Hardrock Mining Act, a bill we supported when it was last introduced in the Senate. We also need to look at long-term water treatment solutions, and we’re going to carefully review our Good Samaritan legislation to make sure we safely encourage more cleanup efforts in these areas.”

Good Samaritan legislation by itself won’t solve the problem, says Lauren Pagel, policy director of the environmental group Earthworks.

“You could have all the good Samaritans in the world, but if there’s not enough money to clean up these sites, then they’re not going to get cleaned up,” said Pagel, whose group backs Grijalva’s reform bill, which would require 8 percent royalties for new hardrock mines and 4 percent royalties for existing mines.

“The idea of nonprofits, local and state governments having to bear the burden of the cost is unrealistic,” she added. “There may be a few mines that are cleaned up that way, but most nonprofits, local and state governments are pretty strapped for cash, so having that steady stream of funding … is really the best way to get as many of these mines as possible cleaned up.”

Stuart Sanderson, president of the Colorado Mining Association trade group, says it’s unfair to charge modern mining companies royalties to fund the cleanup of mines abandoned by other companies that did business in a bygone era when reclamation standards were virtually nonexistent. But he says the industry would support Good Samaritan legislation.

“One of the greatest impediments to the cleanup of these old sites is the absence of any kind of legislation authorizing for Good Samaritan site remediation,” said Sanderson, who wants the modern industry absolved of liability so it can clean up old mines.

“Companies are discouraged from going in and reclaiming these sites because the federal laws, including the Clean Water Act, impose blanket liability for all site conditions,” he added. “In other words, once you touch that site you bought all the liabilities going back to 1890 – all the way back to the very first time that ore was extracted – and that’s just not right.”

Sanderson blames the EPA for the Gold King fiasco and wants industry experts more involved in cleanup efforts, adding environmental groups are using the situation to revisit mining reform.

“It doesn’t surprise me that the groups that are opposed to mining are trying to politicize this debate by opening up the mining law,” Sanderson said. “The environmental groups have insisted upon punitive royalties and other provisions in mining law legislation that would essentially discourage mining on public lands.”

David O. Williams

Latest posts by David O. Williams (see all)

- In governor’s primary race, Bennet, Weiser sparring over who is tougher on Trump - July 15, 2025

- The O. Zone: Battle for public lands just now heating up, much like our atmosphere - July 14, 2025

- Immigrant rights groups push Colorado AG Weiser for probes into violations of ICE collaboration law - July 11, 2025