Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Opinion: Dems darken 50 years of sunshine with legislative super-majority maneuvers

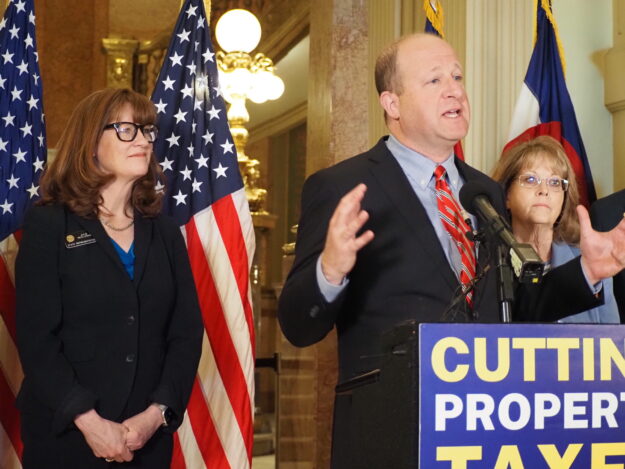

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis speaks during a news conference about a bipartisan property tax reduction bill on May 6, 2024, at the Colorado Capitol, with House Speaker Julie McCluskie, D-Dillon, at left (Quentin Young/Colorado Newsline).

Democrats at the Colorado Legislature are increasingly hostile to open government, and they have learned that they will pay little or no price for drawing a curtain around their work.

But there is a cost, paid by the people. As elected officials block their view of lawmaking, the people’s value as constituents drops. Public servants in America are supposed to be accountable to the people, but if the people can’t see what their government representatives are doing, they have no way to exercise meaningful accountability.

This principle is clearly illustrated as the Legislature prepares to meet next week for a special session on property taxes. During the short session, lawmakers will consider tax cut legislation that was proposed in secret and discussed in the shadows, and it will be debated with the most limited public involvement possible, even though property tax policy affects every resident of the state.

Coloradans might disagree on property tax cuts. But they should be united in demanding transparency.

Homeowners in recent years have seen their taxes increase with rising property values. In May, lawmakers addressed the problem by passing bipartisan legislation that curbed taxes while protecting local districts, including schools, that rely on property tax revenue.

But deep-pocketed conservative groups, including Advance Colorado and Colorado Concern, have used the threat of extreme ballot measures, which would impose district-debilitating property tax cuts, to extract a ransom from state officials. The hostage-taking tactic worked.

Democratic Gov. Jared Polis, Advance Colorado’s Michael Fields and a small group of legislative leaders reportedly met behind closed doors and agreed on the basic terms of further tax cuts. If legislation for the cuts passes, Advance would agree to pull the ballot measures. Polis called lawmakers from around the state back to the Capitol, where Democrats enjoy strong majorities in both chambers, to ratify the deal.

Disdain for transparency peaked when Democrats from the House and Senate met to discuss the deal. They held virtual meetings in secret. Newsline requested recordings of the meetings, but the request was denied.

This behavior appears especially contemptuous of Colorado residents in light of how Democrats earlier this year voided for themselves open-meeting rules that Colorado voters had put in place.

In the early 1970s, during another period when powerful people in state government preferred to conduct business out of view of the public, Coloradans took matters into their own hands and passed an open meetings citizen initiative, spearheaded by pro-democracy group Colorado Common Cause. It was the first “sunshine” law in the country.

The statute and subsequent case law required legislative bodies to hold meetings in public when public business was discussed.

But in March, Democratic lawmakers passed and Polis signed into law a bill that in effect largely exempts the Legislature from open meetings.

One provision of the bill limits the definition of “public business” to formally drafted or introduced legislation and matters before a committee. Previously, a meeting had to be open to the public if its content was connected to the policy-making responsibilities of the legislative body — a much broader standard. In other words, members of the Democratic majority can now meet, talk through, and find consensus on policy outside the view of the Coloradans it will affect, then push through passage of a bill in a process that has only the false trappings of transparency.

That’s what appears to be happening now.

Two Democratic representatives who participated in caucus meetings on the new property tax proposal told Newsline that the meetings involved public business as it was understood until this year.

“Public business was discussed in the meetings. Period. Full stop,” said Democratic state Rep. Elisabeth Epps of Denver, a champion of government transparency. She acknowledged that the new open meetings provisions might have permitted legislative leaders to close the meetings. But she said, “Members of the press, members of the public should have absolutely been allowed at those meetings.”

Special sessions are usually short, and Epps noted that lawmakers won’t have a chance to hear much from people in their communities about the proposed special-session legislation.

Worse, there appears to be a lack of transparency — even for lawmakers.

“A lot of this was baked before we got here,” Democratic state Rep. Steve Woodrow of Denver said. “I think it’s pretty apparent that some type of negotiation was had, and the Legislature was thought of after the fact, if at all, and not included in the process.”

He continued: “As a legislator, we were involved in the process, if you can call it a process, very late, so much so that I think there’s a sentiment on both sides of the aisle that we’re viewed as a rubber stamp.”

If a legislator in the majority is an afterthought in the lawmaking process, that makes the people of Colorado a neverthought.

Advance Colorado is a “dark money” group, which doesn’t have to disclose its donors. Democratic leaders have matched this secrecy with dark lawmaking. That’s not how democracy is supposed to work.

Members of the community can make informed decisions at the ballot box only if they can see elected officials in action. They must be able to observe whether their representatives speak up for their interests, suggest wise proposals, oppose bad ones, interact constructively with colleagues, and generally advance the values that are important to their families. Little of this is possible in the property tax bill “process.”

And the secrecy around the special session is only part of the Democratic assault on the public’s ability to hold government officials accountable. The majority in recent years has conducted an anonymous survey to prioritize bills that cost money, adopted a provision that permits lawmakers to discuss bills entirely in secret through a series of digital communications, and — as Jeffrey Roberts of the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition has noted — refused to address exorbitant public records fees, which effectively block many Colorado residents from access to documents that by right are theirs to view.

In 1972, Coloradans forced state officials to exercise transparency. The Colorado Sunshine Law ballot measure passed by an overwhelming 20 percentage points. Today, Democrats have dragged back to the shadows much of what voters illuminated more than 50 years ago. But, as it was for a previous generation, the citizen initiative process is available to Coloradans who would ensure sunshine when their representatives block it.

Editor’s note: This opinion column first appeared on Colorado Newsline, which is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Colorado Newsline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Quentin Young for questions: info@coloradonewsline.com. Follow Colorado Newsline on Facebook and X.

Buddy Doll

August 24, 2024 at 8:58 pm

Thank you for doing your job. You have to admit, you rarely cross the aisle.