Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Opinion: Remembering the Business Plot, and the first time fascism came to America

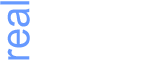

Mussolini prior to his comeuppance.

This Monday marked the 80th anniversary of Benito Mussolini’s last journey: from a village on the shores of Lake Como, where he had been held since his capture the day before, to a farmhouse a little ways to the north, where partisans positioned him in front of a wall and executed him by gunfire. When Adolf Hitler took his own life in a Berlin bunker two days later, it became clear that the first fascist era had come to a sudden, bloody, and well-deserved end.

As World War II wound down, scholarly debates about how to define fascism – the ideological opponent which had recently ravaged Europe – raged on. Some have always erred towards a minimalist definition, confining their understanding of fascism to the particulars: an Italian authoritarian-corporatist political movement of the early 20th century. Merriam Webster, thankfully, goes a bit broader, offering the definition that fascism is “a populist political philosophy, movement, or regime…that exalts nation and often race above the individual, that is associated with a centralized autocratic government headed by a dictatorial leader,” and so on.

In the years I have spent obsessively attempting to understand the movement, personally, I have not come across better definitions than those offered by Oxford-based political theorist Roger Griffin’s palingenetic ultranationalism, or Italian scholar Umberto Eco’s 14-point definition of what he called Ur-Fascism. If I were to dedicate this entire discussion to parsing the different definitions of fascism, though, there’s good reason to believe that it might take another 80 years.

Between the end of World War II and the last few years, the popular American understanding of fascism was shaped less by scholarly definition, though, than by a series of patriotic myths. We believed that fascism was something done by monsters like Hitler and Mussolini, and that it was vanquished after World War II. We believed that it never set foot upon American soil, and that, if it did, it would instantly wither in the harsh glare of liberty. We believed that fascism was something which affected other peoples, elsewhere, and that Americanism was its natural antidote.

Today, many of us know those beliefs to be wrong. In the absence left by the shattering of those naive beliefs, though, many still struggle to conceive of fascism as something which can be grown in American soil. We comfort ourselves by thinking it had to have been imported from elsewhere – that, for instance, it all stemmed from Russian meddling in the 2016 elections. But Russian interference, though real, did not make the United States capable of something it was not previously capable of. If anything, it just helped uncover what has always been there: a homegrown, American version of fascism which reared its ugly head here, in the United States, long before Mussolini and Hitler’s deaths, before the Nazis ever rose to power in Germany.

If we cannot understand what we are capable of, we will never successfully defeat it. That’s why I spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about a chilling episode from American history which most of us were never taught about in school: the time American businessmen plotted a fascist coup against the government of the United States, and almost carried it out.

The year was 1933. The Great Depression was on, civil unrest was afoot, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt had just been sworn into the Presidency. The country was swimming with out-of-work World War I veterans, and the financiers and industrialists were worried about FDR’s rise to the Presidency, concerned that it would result in higher taxes and greater regulations for their business interests. That’s when a man presented himself to retired Marine Corps Major General Smedley Butler with a plan.

The plan, hatched by American tycoons like J.P. Morgan, Jr., investment banker Grayson Murphy, and Singer Corporation heir Robert Sterling Clark, was to put those out-of-work veterans to use in the cause of overthrowing FDR, preventing the New Deal, and bringing a fascist dictatorship to America. Adding to the fire, the cabal behind what is now known as the Business Plot had already secured the support of leaders in the country’s largest veterans organization, the American Legion, in their quest. Morgan and the others, the man told Butler, would pay some 500,000 veterans to march on Washington, D.C. and overthrow the government. With a plan based on Mussolini’s own successful March on Rome, the backing of select American Legion leaders, and financing from some of the nation’s wealthiest citizens, the Business Plot was more than idle chatter. All they needed was a figurehead.

The plotters had good reason to choose Butler: he was a seasoned pro at using state power to protect and enhance business interests. During his 33-year career in the Marine Corps, Butler had paved the way for the light of capitalism from one end of the world to the other, fighting for American business interests in the Philippines, China, Honduras, Nicaragua, and a score of other countries. Unfortunately for the cabal, they didn’t bring their fascist plot to Butler until after his Road to Damascus moment.

As he approached the end of his military career a few years earlier, Major General Smedley Butler experienced a crisis of faith; not religious faith, but faith in the work he had spent his life doing, and the forces he had done it for. By the early 1930s, Butler was increasingly critical of monopolists, militarists, and war-profiteers. In fact, in 1931, while he was still in uniform, Butler was arrested and court-martialed for criticizing Mussolini – then a U.S. ally – in a speech. He retired later that same year as an avowed opponent of fascism, and found himself increasingly worried that his entire career had been spent in service to some form of it.

In 1935, two years after the Business Plot had come and gone, Butler committed his change of heart to the page, authoring the book War is a Racket, and describing his own 33-year career in the Marines as that of a “gangster for capitalism.”

“I helped make Mexico and especially Tampico safe for American oil interests in 1914,” Butler wrote. “I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefit of Wall Street. I helped purify Nicaragua for the International Banking House of Brown Brothers in 1902-1912. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for the American sugar interests in 1916. I helped make Honduras right for the American fruit companies in 1903. In China in 1927 I helped see to it that Standard Oil went on its way unmolested. Looking back on it, I might have given Al Capone a few hints.”

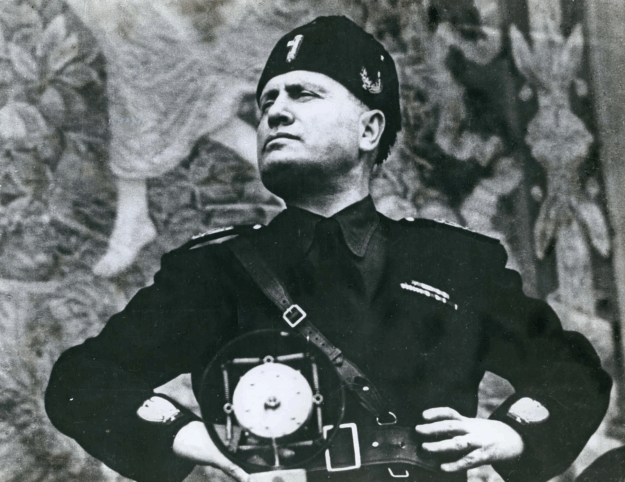

All that to say, by the time the coup plotters presented their idea to the man they hoped would tie it all together – the man they hoped would mobilize the veterans they had organized, march them into Washington, D.C., and name himself a dictator – they had the wrong man. Instead of going along with the plan, Butler went to Congress and promptly raised the alarm, triggering a two-year investigation. What the New York Times originally referred to as a “hoax” was substantiated so thoroughly by the subsequent Congressional investigation that the same paper was later compelled to report that the committee believed “definite proof had been found” of the plot.

The Business Plot failed, the New Deal succeeded, and World War II eventually rewrote America’s conception of fascism as something which happens elsewhere, something anathema to Americanism. Slowly, the coup plan left the collective memory, taking along with it the hard-earned knowledge of how unrestrained business interests fuel our particular American iteration of fascism, and the cost we almost paid for it once before.

The New York Times, Nov. 21, 1934.

Now, in the absence of collective memory, we have arrived again at the doorstep of danger. Unrestrained oligarchs exercise unlimited power over American politics, a racist, revanchist nationalism is once again sweeping the country, and the business interests at the top don’t mind one bit what happens next, as long as it profits them.

In coddling our national psyche with a series of patriotic myths about fascism, we left ourselves exposed to the same root causes which grew into an attempted fascist overthrow of the United States government once before. The inequality. The racial resentment. The unrestrained business interests. Now those roots are sprouting again and, if we are ever going to see the end of that horrible fascist spring, we must understand that they grew in our soil. We must take pains to understand our present circumstances not as something other, something from elsewhere, but as something we bred and as something we can end.

The first fascist era ended in gunfire, at a farmhouse in Lombardy and then in a bunker in Berlin. We don’t know where the second will end, but the good news is that we can be fairly certain it will: no regime has lasted forever. The only open question is what it will cost to get to that inevitability, to cross the distance between here and there.

When it does end, when the time comes to build a better, more equal, more resilient republic, we need to remember to pull up the roots, to salt every inch of ground which has ever proven fertile for fascism in this country. Because, if we don’t, we’ll be back here again a few decades later, tangled in thickets we grew.

Editor’s note: This opinion column first appeared on the Colorado Times Recorder website. Logan M. Davis is a progressive researcher and writer based in Denver, specializing in the threat posed by right-wing extremism. He is also a political communications consultant. He is a proud member of Denver NewsGuild and co-founder of the Political Workers Guild of Colorado.